Packaging Formats for Bulk Walnuts: Bags, Cartons, and Liner Choices

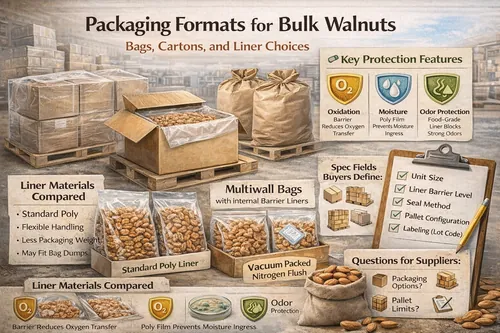

Industrial buyer guide to bulk walnut packaging formats—how to choose between bags, cartons, and liner types to protect quality, reduce oxidation drift, and make receiving/handling easier. Includes packaging spec fields, barrier and seal considerations, palletization and export notes, receiving inspection checklist, and supplier questions for bulk walnut programs.

Previous: Allergen Controls for Bulk Walnut Programs: Receiving, Storage, and Labeling • Next: Retail Packaging Programs for Walnuts: Private Label and QC Points

Related: bulk walnut products • products catalog • request a quote

Why packaging matters for bulk walnuts

In industrial procurement, packaging is not just a shipping container—it’s a quality control tool. For walnuts, packaging influences how quickly a lot can drift in storage and transit, how often it gets exposed to oxygen after opening, and how well it is protected from moisture events and odor pickup.

- Oxidation control: oxygen exposure and warm temperatures increase rancidity risk and “stale oil” notes over time.

- Moisture protection: humidity events can soften texture, change handling performance, and increase defect sensitivity.

- Odor protection: walnuts can pick up strong warehouse or freight odors if packaging is weak or repeatedly opened.

- Foreign material protection: punctures, broken seals, and damaged cartons increase contamination exposure.

- Operational efficiency: the “right” format reduces rework, spills, staging time, and ergonomic pain.

Procurement reality: Two lots with identical grade names can perform differently if packaging and liner systems differ. For shelf-life sensitive programs, packaging format is a first-order decision—not an afterthought.

How to choose a bulk walnut packaging format (buyer framework)

The fastest way to select a packaging format is to align it to your use case, throughput, and storage posture. Most buyer issues come from choosing packaging for “lowest cost” when the plant actually needs lowest exposure (oxygen/moisture/handling damage) or lowest handling friction.

Start with these questions

- What is the walnut format? kernels/halves, pieces, meal/flour, paste/butter, or oil (each behaves differently).

- How fast will you consume each container? throughput drives pack size and reseal needs.

- Is the application flavor-sensitive? mild bases and premium snacks show oxidation earlier.

- How long is the storage + transit window? long holds and warm lanes increase the value of higher barrier packaging.

- What does receiving look like? forklift handling, decanting system, bin dumpers, and staging space matter.

Common “fit” signals

- Cartons + liners often fit best when stacking stability, puncture protection, and clean warehouse handling matter most.

- Bag formats can fit when you have controlled handling systems and want packaging weight reduction or different pallet density.

- Higher barrier liners fit when shelf-life sensitivity is high or when product sits open in partial containers.

- Smaller units fit when consumption is slow and exposure after opening is a major complaint driver.

Common bulk packaging formats for walnuts (what buyers see in the market)

Bulk walnut programs typically use a small set of proven packaging formats. Your supplier may offer several options depending on the product form (halves vs pieces) and whether the lane is domestic, export, or private label / contract packing.

1) Corrugated cartons with food-grade liners

This is one of the most common formats for walnut kernels and pieces because it protects against punctures and improves stacking stability. Cartons also make lot-code labeling and pallet configuration consistent.

- Best for: kernels/halves, pieces; warehouses that prefer clean stacking and lower puncture risk.

- Strengths: stackability, protection, easy labeling, clean receiving.

- Watchouts: liner choice and seal method still determine oxygen/moisture exposure; carton damage still matters.

2) Multiwall bags (paper or poly systems) with internal liners

Bag formats can work well when your plant has established bag handling systems. They can reduce packaging weight and sometimes fit specific pallet patterns. The practical risk is puncture damage and inconsistent reseal discipline after opening.

- Best for: high-throughput plants with controlled handling and quick consumption.

- Strengths: flexible handling, potential packaging weight reduction, can fit certain dump stations.

- Watchouts: punctures, spill risk, and odor/moisture exposure if staging is not disciplined.

3) Bulk bags / “super sacks” (program-dependent)

Bulk bags can reduce labor in very high throughput settings, but they require suitable infrastructure (lifts, docks, controlled staging), and they tend to magnify the consequences of a single packaging failure.

- Best for: very high volume operations with equipment to support safe handling and controlled environments.

- Strengths: fewer unit touches, lower packaging per pound, fast charging into process.

- Watchouts: if product sits open, oxidation risk rises quickly; damage events are costly.

4) Drums or totes (more common for oils/pastes; sometimes for specific walnut formats)

Drums and totes are common for walnut oil and butters; they can also appear in specialized programs where contamination protection is prioritized.

- Best for: walnut oil, walnut butter/paste; specialty programs requiring robust containment.

- Strengths: strong physical protection, controlled closures, easier reseal than sacks.

- Watchouts: higher unit cost and return logistics (for reusable totes) depending on program.

Rule of thumb: If your biggest issue is damage, spills, or dirty receiving, cartons often win. If your biggest issue is oxidation after opening, pack size and liner barrier usually matter more than “bag vs carton.”

Liner choices: oxygen barrier, moisture barrier, and odor protection

For bulk walnuts, the liner does most of the real work. Cartons and outer bags provide structure and puncture resistance, but the liner determines how much oxygen and moisture reach the kernels over time and how exposed the product is to warehouse odors.

What buyers mean by “liner quality”

- Material: common food-grade plastics (single layer or multi-layer constructions).

- Barrier performance: how well the liner reduces oxygen and moisture transfer.

- Thickness and puncture resistance: affects leak/puncture risk and seal strength.

- Closure method: heat seal, tie, tape, or other system (closure often matters as much as the film).

Typical liner “tiers” buyers see

Note: suppliers may describe liners differently. The practical action is to define the outcome you need (barrier/seal discipline), not to over-specify brand names unless your program requires it.

| Liner tier | What it’s optimized for | Typical fit |

|---|---|---|

| Standard poly liner | Basic containment and moisture event protection | Fast-turn programs; robust applications; controlled storage |

| Improved puncture / thicker liner | Handling resilience and seal reliability | Rough handling lanes; mixed warehouses; longer transit |

| Higher barrier liner (multi-layer) | Reduced oxygen transfer and odor pickup | Flavor-sensitive programs; long shelf-life; warm lanes |

| Vacuum / gas-flush capable system | Minimizing headspace oxygen and reducing drift after packing | Premium snack / visible inclusions; long distribution; strict complaint posture |

Practical liner details that prevent disputes

- Define what “sealed” means: heat seal vs tie; single vs double seal; and what is acceptable at receiving.

- Clarify odor protection expectations: especially if your warehouse stores chemicals, flavors, or cleaning agents nearby.

- Align barrier to shelf life: if your product sits for months, barrier and seal integrity often pay for themselves.

Seal integrity: the cheapest failure mode in bulk walnut programs

Many “quality” complaints originate from simple packaging failures: broken seals, punctures, or liners left loosely closed after sampling. Seal integrity matters at three moments: after packing, during transit, and after opening.

What buyers should specify and enforce

- Packaging must arrive sealed: define acceptable closures and what constitutes a reject condition.

- Sampling discipline: if you sample at receiving, define how liners are resealed and how partial units are staged.

- No “tape-only fixes”: define whether taped punctures are acceptable (many programs treat as rejectable).

- Water damage policy: clearly define acceptance criteria for wet cartons or damp pallets.

Buyer tip: If you can only control one packaging KPI, control seal integrity. A high-barrier liner with a poor seal behaves like a low-barrier liner.

Pack size strategy: reduce oxidation after opening

Even the best packaging loses value if walnuts sit open in partial containers. Pack size should match your consumption rate so that once a unit is opened, it is used quickly—or resealed and staged in a controlled way.

When to use smaller units

- Slow-use ingredients: seasonal SKUs or specialty inclusions.

- High sensitivity to flavor drift: mild bases, premium snacks, delicate bakery toppings.

- Many line changeovers: frequent opens increase exposure events.

When larger units can work

- High throughput: the unit is consumed quickly after opening.

- Controlled staging: cold/controlled rooms and disciplined reseal procedures exist.

- Robust applications: where minor drift does not show up in finished product.

Practical approach: estimate how many hours a unit stays “open” on your floor. If that time is long, prioritize smaller units or reseal-friendly packaging to reduce oxidation drift.

Palletization and logistics: packaging choices that reduce damage

Many packaging issues are actually logistics issues: overhang, weak stacking, crushed bottom layers, or punctures from pallet damage. Your packaging spec should include palletization fields so every shipment looks the same and receiving can move fast.

Common palletization fields to define

- Units per pallet: consistent count and layer pattern.

- Max pallet height: match your racking, trailers, and container constraints.

- Stretch wrap / corner boards: define stabilization expectations for long lanes.

- No overhang: overhang increases crush and puncture risk.

- Lot segregation: define whether a pallet can mix lots (many programs require one lot per pallet).

Damage modes to watch for in bulk walnuts

- Crushed cartons: often caused by overstacking or weak layer patterns.

- Punctured liners: forklift tines, broken pallets, or sharp carton edges.

- Water damage: condensation, wet docks, or transit exposure—define acceptance rules.

Export and long-lane notes: when packaging needs to be “more than adequate”

Export or long domestic lanes increase the value of stronger packaging systems because the product experiences more time, more handling touches, and more temperature swings. Even without “temperature abuse,” the additional days or weeks increase exposure to drift.

Typical export/long-lane packaging considerations

- Higher barrier liners: often justified by longer time-to-use and more variable environments.

- Improved stabilization: corner boards, tighter wrap standards, and robust pallet patterns.

- Pallet treatment requirements: some destinations require treated pallets; confirm early if applicable.

- Container loading discipline: avoid crushing, avoid odor loads, and reduce moisture exposure risks.

If your destination lane is warm or long, packaging and storage controls are often a better investment than trying to “buy fresher lots” alone.

Packaging spec fields buyers should include (copy/paste friendly)

A good packaging spec is short, measurable, and aligned to receiving inspection. Below is a practical checklist you can translate directly into an RFQ or spec sheet.

Core packaging specification fields

- Product + format: walnut kernels (halves), kernels (pieces), meal/flour, etc.

- Package type: carton w/ liner, bag w/ liner, drum, tote, bulk bag (if applicable).

- Net weight per unit: define the unit weight and tolerance expectations if required.

- Liner requirement: food-grade liner; barrier tier (standard vs higher barrier) if your program is shelf-life sensitive.

- Closure method: heat seal / other closure; define “sealed on arrival” requirement.

- Labeling + lot codes: lot code location and readability; match to COA and shipping docs.

- Pallet configuration: units/layer, layers/pallet, pallets/load, max height, no overhang.

- Stabilization: stretch wrap expectation; corner boards if required; slip sheets if used.

- Export requirements: pallet treatment notes, destination label needs, and any documentation linkage.

Example spec language (simple and enforceable)

- Seal integrity: “All units must arrive sealed and intact; punctures, broken seals, or water-damaged packaging are rejectable.”

- Lot traceability: “Lot code must be visible on every unit and must match COA and shipping documents.”

- Odor protection: “Packaging must protect against odor pickup; product must arrive free of foreign odors.”

Buyer framing: If a packaging detail cannot be checked at receiving, it’s hard to enforce. Prioritize specs that map to a receiving checklist and prevent downstream disputes.

COA and documentation fields that support packaging acceptance

COAs typically focus on product quality (moisture, defects, etc.), but for packaging-driven programs you also want documentation that helps receiving teams validate lot identity and traceability quickly.

Documentation fields buyers commonly request

- Lot identification: must match unit labels and pallet tags.

- Product description: format (halves/pieces) and any program notes (raw/roasted, etc.).

- Moisture: especially relevant if packaging is designed to protect texture and shelf-life posture.

- Country of origin: for compliance and labeling workflows.

- Allergen statement: walnut declaration aligned to labeling needs.

- Traceability identifiers: production/shipment identifiers to isolate issues if a packaging failure occurs.

- Any required compliance docs: availability varies by supplier program and destination.

If your program has strict pallet or unit labeling requirements, send a label photo or mockup early—small mismatches create big receiving delays.

Receiving inspection checklist for bulk walnut packaging

Use a packaging-focused checklist to prevent “slow drift” problems (oxidation, odor pickup) and to catch obvious failures (punctures, water damage) before product enters your warehouse.

Packaging and handling checks

- Seal integrity: liners closed as specified; no broken seals, open liners, or “re-taped” punctures.

- Punctures and abrasion: inspect corners and bottom layers; check for liner contact points.

- Water damage: wet cartons, staining, warped bottoms; define disposition rules ahead of time.

- Odor exposure: sniff test at opening; watch for chemical, perfume, diesel, or musty notes.

- Labeling and lot code: readable and consistent; matches COA and shipping documents.

- Pallet stability: no collapsed corners, major overhang, or crushed layers.

Product-level checks tied to packaging performance

- Odor and freshness: clean walnut aroma; no painty, rancid, musty, or stale notes.

- Visual check: obvious foreign material or excessive crumbs (can indicate rough handling).

- Moisture verification: if your program is texture-sensitive or if shipment experienced humid conditions.

- Retains: keep a retained sample by lot for shelf-life tracking and complaint investigation.

QA tip: If you have recurring oxidation complaints, track one additional data point: “estimated hours of open exposure” from first opening to final use. Pack size and reseal discipline often emerge as the true driver.

Questions to ask suppliers (packaging-focused)

Questions that map directly to oxidation and damage risk

- What packaging options are available for this walnut format? Carton/liner systems, bags, unit sizes.

- What liner tier is standard vs optional? Clarify barrier intent and closure method.

- How are liners sealed? Heat seal vs tie; and what “sealed on arrival” means in practice.

- What are typical pallet patterns and stabilization methods? Units per pallet, max height, corner boards if used.

- What is your damage/claims process? Photos required, timelines, disposition rules.

Questions that reduce receiving friction

- Where are lot codes printed and how are pallets labeled? Prevent “can’t find the lot code” receiving delays.

- Can lots be kept single-lot per pallet? Helpful for traceability and inventory control.

- What documentation is available? COA, allergen statement, country of origin, traceability identifiers.

- How is product stored pre-ship? Storage posture influences flavor stability and how much packaging barrier matters.

Tight packaging specs can increase cost, but they often reduce hidden costs: rework, complaints, shelf-life failures, and line disruptions. The best approach is to match packaging investment to your sensitivity and lane exposure.

FAQ: bulk walnut packaging formats

Is vacuum or gas flushing always necessary for bulk walnuts?

Not always. Many industrial programs succeed with standard liners if inventory turns are fast and storage is cool and dry. Vacuum or gas-flush capable systems tend to add value when shelf-life targets are long, the lane is warm/variable, or the application is flavor-sensitive.

Do cartons protect quality better than bags?

Cartons often reduce puncture risk and improve stacking stability, which indirectly protects quality by reducing exposure events. But oxygen and moisture control largely come from the liner and seal integrity, and oxidation after opening depends on pack size and reseal discipline.

What is the most common packaging-related cause of complaints?

Broken seals, punctures, and long open exposure after opening are common drivers. If walnuts sit open in partial containers, oxidation drift can increase even when the incoming lot was strong.

How should we store opened containers?

Reseal promptly, minimize oxygen exposure, and stage in a cool, dry area away from strong odors. Use pack sizes that match consumption rate whenever possible.

Next step

If you share your walnut format (halves/pieces/meal/oil), application (snacks/bakery/confectionery/dairy), target shelf life, your storage posture (cool storage vs ambient), and your preferred receiving workflow (cartons vs bags, unit sizes, pallet limits), we can recommend practical packaging formats and liner choices that match your program. Use Request a Quote or email info@almondsandwalnuts.com.

For sourcing, visit bulk walnut products or browse the full products catalog.