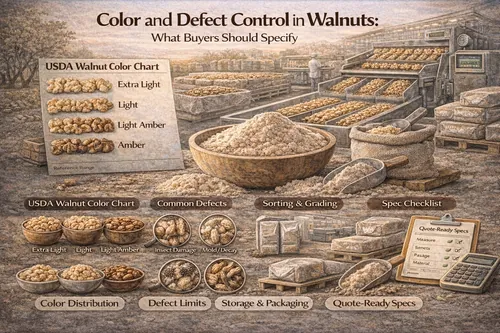

Color and Defect Control in Walnuts: What Buyers Should Specify

Walnut quality is not only “how it tastes.” For industrial buyers, the biggest acceptance drivers are often kernel color distribution and defect control—because those two variables predict how a lot will perform in manufacturing, how it will look in a finished product, and how much rework (or rejection risk) you carry at receiving. This guide breaks down what color and defect actually mean in practical procurement terms, what causes drift from field to warehouse, and how to write quote-ready specs that protect consistency.

Previous: Shelling and Sorting Walnuts: How Halves/Pieces Grades Are Produced • Next: Storage and Oxidation Control for Walnuts: Temperature and Oxygen Management

Related: bulk walnut products • products catalog • request a quote

Why walnut color and defects matter to buyers

In bulk walnut procurement, “quality” is often judged at receiving with a fast visual inspection and a few key tests. That reality makes color distribution and defect rates the most consequential levers for:

- Finished-product appearance: light kernels are preferred in premium snacks, bakery toppings, and confectionery where walnuts are visible.

- Process yield: high defect or foreign material rates mean higher rework, trimming, sorting, and line stoppages.

- Brand risk: moldy, rancid, or insect-damaged kernels can cause customer complaints even if the rest of the lot is acceptable.

- Cost predictability: the cheapest offer can become expensive if it raises rejection rates or requires additional in-plant sorting.

Practical rule: If walnuts are visible in your product, tighten color distribution. If walnuts are milled or used as an inclusion where appearance is less critical, focus your spec energy on rancidity risk, foreign material, and micro.

How walnut color is defined (and how to write a usable spec)

In U.S. trade language, walnut kernel color is commonly described with the USDA color classifications: extra light, light, light amber, and amber, referenced to the USDA Walnut Color Chart. In USDA standards, the color classification is defined by the darkest allowable shade within the selected class. (The “red” classification exists but is typically treated separately in trading language.) The official classification framework is codified in U.S. standards and regulations.:contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}

The trap: “Light amber” alone is not a distribution

Many buyers put “light amber” on a spec and assume they will receive mostly light kernels. But “not darker than light amber” can still include a meaningful range of tones inside that band. For visible applications, you often need a distribution requirement, not only a maximum darkness.

Better: specify a practical color distribution

A quote-ready color spec typically includes:

- Maximum darkness: e.g., “not darker than light amber” or “not darker than light.”

- Minimum % in lighter classes: e.g., “≥ X% not darker than light” and “≤ Y% amber.” (Industry charts commonly show example allowances for “light,” “light amber,” and “amber” style packs.):contentReference[oaicite:1]{index=1}

- Method alignment: confirm whether the supplier uses color boards, trained graders, or optical systems tied back to standard references.

Buyer tip: Color specs should match your use case. Premium snack or bakery topping? Tighten color. Chocolate inclusions or paste? You can relax color and redirect budget toward oxidation control and defect reduction.

What drives walnut color drift from orchard to warehouse

Walnut color is influenced by orchard conditions, harvest timing, and post-harvest handling. The key point for buyers: color is not “cosmetic only”—it is a signal that the lot experienced certain conditions that can also affect flavor stability.

1) Harvest timing and time-to-hulling

Delays between harvest operations (picking/collecting) and hulling can accelerate kernel darkening, especially in hot conditions. Extension guidance emphasizes avoiding delays and coordinating harvest with drying capacity because warm conditions speed browning.:contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}

2) Drying control (temperature and end moisture)

Drying is not just about “getting walnuts dry”—it’s about drying without cooking or darkening kernels. UC/industry guidance commonly notes that adequately dried walnuts should be at or below about 8% moisture, and that drying air temperature should be controlled (with recommendations such as not exceeding about 110°F / 43°C) to reduce quality damage and browning.:contentReference[oaicite:3]{index=3}

3) Weather and field conditions

Rain events near harvest, high humidity, and longer ground contact can increase staining, mold risk, and darker kernels. You don’t need to be an agronomist to buy well—but you should know that “color lots” can be seasonally influenced. That is why experienced buyers align launch windows and spec strictness to crop-year realities.

4) Storage conditions and oxidation exposure

Kernel color can continue to shift during storage, especially with temperature swings and oxygen exposure. Cold and stable storage helps. Guidance references an optimum storage temperature range (commonly cited around 32–50°F) with controlled relative humidity to help maintain quality and reduce browning.:contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4}

Defect types buyers should control (and why they show up)

“Defects” are the practical reasons a lot fails inspection, causes customer complaints, or creates line headaches. USDA standards define defect concepts and tolerances for graded product, and the language used in trade often maps back to these definitions.:contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5}

Defects that impact food safety and acceptance first

- Mold / decay: visible mold, decay, or musty odor. Often linked to poor drying, moisture pockets, or high-humidity storage.

- Rancidity / off-odors: painty, stale, bitter, or “old oil” notes. Driven by oxidation, warm storage, and long oxygen exposure.

- Foreign material: shell fragments, stones, wood, plastic—anything not walnut. This drives immediate rejection risk and recalls.

Defects that drive appearance, yield, and process loss

- Discoloration / dark spots: may be acceptable in paste or inclusions but problematic in visible applications.

- Shrivel: reduces “plump” appearance and perceived quality; can increase breakage and dust.

- Insect injury: feeding damage, holes, webbing—creates rejection risk and negative perception.

- Mechanical damage: crushed pieces, excessive fines, broken halves—often tied to shelling settings and handling.

Buyer tip: If you’re buying pieces, you still need a “shape” spec (e.g., piece size distribution + max fines). Otherwise, yield and dosing can drift even if the lot “passes” a basic COA.

Sorting and grading: what suppliers can control (and what you can buy)

Walnut programs typically separate kernels by style (halves, pieces, etc.), size, color, and defect class. The more you ask to tighten, the more the supplier must sort, re-sort, and remove marginal product—so tighter specs usually increase price but reduce your internal risk and labor.

Common sorting tools (high level)

- Screening / sizing: separates kernels by size and reduces fines.

- Aspiration / air separation: removes lighter debris and helps reduce foreign material.

- Gravity separation: can help separate light defect material from good kernels.

- Optical sorting: detects color defects, dark kernels, and certain foreign materials; often used for tighter “light” programs.

- Hand sorting: used as a final tightening step in premium packs or where optical detection is insufficient.

How to talk to suppliers so you get the lot you expect

- State your application: “visible topping” vs “inclusion” vs “paste” changes the right color/defect tradeoffs.

- Define your non-negotiables: foreign material, mold/decay, rancidity gates, and maximum amber content.

- Ask what can realistically be controlled run-to-run: especially if you need tight color distribution in a variable crop year.

QA checkpoints: what to test, what to monitor, and what to put on a COA

A strong QA program combines in-process monitoring (so drift is caught before a full lot is produced) and finished-lot release (so your receiving spec matches what ships). Below are common checkpoints buyers request for industrial walnut programs.

Receiving-critical (high impact) items

- Color distribution: agreed classification and any % requirements (especially for “light” programs).

- Defect limits: mold/decay, insect injury, shrivel, discoloration, excessive fines (as applicable to style).

- Foreign material & shell: explicit limit and method expectation (screen/metal detect/optical program dependent).

- Moisture: keep consistent to reduce spoilage risk and processing drift; guidance references ~8% max for adequately dried walnuts.:contentReference[oaicite:6]{index=6}

Oxidation / rancidity gates (program dependent)

For shelf-life sensitive programs (retail packs, long export transit, premium snacks), consider requesting oxidation-related checks. Industry handling guidance may include target limits for measures such as peroxide value and free fatty acids as practical indicators of freshness and oil breakdown.:contentReference[oaicite:7]{index=7}

Micro and allergen documentation

- Micro program: depends on your category and downstream kill steps (if any).

- Allergen statement: walnuts are a tree nut; confirm statement language needed for your markets.

- Traceability: lot code, crop year, and COO as needed for audits and recalls.

If your customer rejects for “appearance,” your receiving plan should include a quick color/defect visual gate before the lot hits production. It is cheaper to stop a problem at the dock than to rework finished goods.

Storage and packaging: keep the “good lot” good

Even strong harvest quality can be undermined by storage and handling. Walnuts are sensitive to oxidation and odor pickup, so your storage and packaging strategy should match the time your inventory will sit before use.

Storage levers that reduce quality loss

- Temperature stability: cool, stable storage reduces oxidation rate; guidance commonly references cold storage ranges such as 32–50°F for quality retention.:contentReference[oaicite:8]{index=8}

- Humidity management: prevent moisture swings that can encourage mold risk or texture drift.

- Odor control: keep walnuts away from strong-smelling materials (spices, chemicals, fragrances).

- FIFO discipline: walnuts are not “set and forget”; align inventory turns to your shelf-life posture.

Packaging options for bulk programs

Packaging should match your receiving equipment, re-pack needs, and shelf-life risk posture:

- Lined cartons / bags: common for kernels; specify liner type and barrier needs when shelf-life is critical.

- Vacuum or gas-flush (program dependent): may reduce oxygen exposure for longer shelf-life targets.

- Bulk bags: efficient for high-volume ingredient programs; confirm pallet constraints and handling method.

- Export planning: align barrier and palletization with transit time and destination warehouse conditions.

Share: maximum pallet height, dock constraints, whether you break pallets, and whether you re-pack—these details affect what packaging is practical and economical.

Specs checklist (quote-ready): what to send so suppliers can price accurately

If you already have a spec sheet, send it. If not, this checklist usually gets to a clean quote with fewer back-and-forths:

1) Product identity

- Product: Walnut kernels

- Style: halves, pieces (specify cut size distribution if pieces), or specific style nomenclature used in your plant

- Crop year preference: current crop vs flexible (if relevant to your quality posture)

2) Color specification (make it unambiguous)

- Max darkness: extra light / light / light amber / amber (USDA color chart reference):contentReference[oaicite:9]{index=9}

- Distribution requirement: minimum % not darker than light; maximum % amber (if appearance is critical)

- End-use note: “visible topping” vs “inclusion” vs “paste”

3) Defect and foreign material limits

- Defect limits: insect injury, mold/decay, shrivel, discoloration, excessive fines (as applicable)

- Foreign material / shell: explicit limit + method expectations (screening, detection, optical program)

- Sensory: “no rancid/off odor” gate and (optionally) PV/FFA targets for shelf-life sensitive programs:contentReference[oaicite:10]{index=10}

4) Moisture and QA requirements

- Moisture target: specify your acceptable range and the receiving method; guidance commonly references ~8% max for adequately dried walnuts:contentReference[oaicite:11]{index=11}

- Micro requirements: as applicable to your category and customer requirements

- Documentation: COA, traceability, COO, certifications if required

5) Packaging, volume, and logistics

- Packaging: bag/carton/bulk bag; liner expectations; pallet configuration limits

- Volume: first order + forecast; delivery cadence

- Destination: city/state/country; required delivery window; export documentation needs (if any)

- Receiving constraints: pallet height limits, dock hours, equipment, and whether you re-pack

If your brand rejects for appearance, add: “critical-to-quality = color distribution and max amber” so the supplier can quote the correct sorting intensity (and you avoid surprises on arrival).

FAQ: quick buyer answers

What color should I buy for walnuts used as an inclusion?

If walnuts are mixed into a product where consumers don’t visually judge each kernel (bars, granola clusters, fillings), you can often accept a wider color range (e.g., up to light amber) and invest savings into tighter defect and oxidation control. If walnuts are a visible topping, tighten color distribution.

Should I always buy “light” walnuts for premium quality?

Not necessarily. “Light” can be right for premium visual applications, but you still need to control defects, rancidity risk, and foreign material. Some “light” lots can be over-sorted but still carry oxidative age if storage and packaging were weak.

What’s the easiest way to reduce rejection risk?

Put the right non-negotiables on the quote: explicit color distribution (if needed), clear defect limits, foreign material limits, moisture range, and a simple sensory gate (no rancid/off odors). Then align packaging and storage to your shelf-life target.

Do moisture and drying really affect color?

Yes. Handling guidance emphasizes that drying control and adequate dryness (often referenced as not more than about 8% moisture) help prevent deterioration and darkening, and that drying air temperature control matters.:contentReference[oaicite:12]{index=12}

What sources define walnut color classifications?

USDA standards define the color classifications (extra light, light, light amber, amber) by reference to the USDA Walnut Color Chart.:contentReference[oaicite:13]{index=13}

Want a faster spec? Send your end use + a photo of your “ideal” walnut appearance, and we can translate it into a workable color distribution + defect spec for quoting.

Next step

Share your application (snack, bakery topping, confectionery inclusion, paste), your target color distribution, and your defect tolerance. We’ll recommend a practical spec, align packaging and documentation, and confirm the fastest supply lane. Use Request a Quote or email info@almondsandwalnuts.com.

References (for buyers building internal specs): USDA walnut grade and color definitions:contentReference[oaicite:14]{index=14} • California/UC handling and storage guidance:contentReference[oaicite:15]{index=15}